Retail traders are losing billions in India’s booming options market

Like a movie star at a premiere, Mohammad Nasiruddin Ansari steps out of the back seat of a white Mercedes. Flanked by a phalanx of black-clad bodyguards, he strides into the lobby of a luxury hotel and takes center stage in a ballroom as indoor fireworks machines spew fountains of sparks. “If you don’t make money in three months, I will give you 2 million rupees [$24,000],” he declares to cheers from the adoring crowd in a scene that’s still playing on YouTube.

Ansari is meeting his fans in Pune, about 90 miles south of Mumbai.He’s selling the dream of stock market riches to India’s fast-growing cadre of small investors. With half a million social media followers, he’s pushing an especially risky strategy: trading stock options, often as all-or-nothing bets on future share prices.

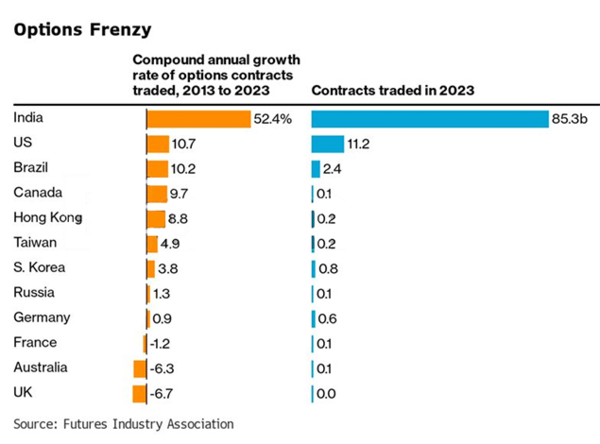

In 2023, Indian investors traded 85 billion options contracts, more than anywhere else in the world. The country has topped the charts since 2019, when it first overtook the US in the volume of annual trades. (The US still buys and sells the most by dollar value.)

At conferences like Ansari’s, promoters, or influencers, encourage the rank and file to get their piece of one of the world’s best-performing economies and stock markets. Video courses flood the internet with catchy titles: “Become a PRICE ACTION Beast.” “Easy Options.” “Options Trading Tricks.” “Best Scalping Strategy Ever.” “Become a Supply & Demand ‘SNIPER.’ ”

In India retail investors make up 35% of options trades. Institutions, seeking to hedge their risk or profit for their companies’ accounts, handle the rest. Regulators are alarmed that regular folk are bypassing the tried-and-true way to build wealth: buying and holding stocks and mutual funds.

Instead they’re engaging in pure speculation. The average time an Indian trader holds an option is less than 30 minutes, according to data from mutual fund provider Axis Asset Management Co. “If you want to gamble, if you need diabetes and high blood pressure, then go into this market,” Ashwani Bhatia, a board member on the nation’s top stock market regulator, said last year.

His agency, the Securities and Exchange Board of India, known as Sebi, says 90% of active retail traders lose money trading options and other derivative contracts. In the year ended March 2022, the latest for which figures are available, investors lost $5.4 billion. That amounted to $1,468 apiece, no small matter in a country with a per capita gross domestic product that year of $2,300.

A common strategy among traders involves wagering on Indian stock indexes, such as the benchmark Nifty 50. Consider the risk. Buying a contract gives you the right to buy certain units of the index at a “strike” price—a call option. On January 3 you could’ve bought Nifty 50 options expiring the next day for 25¢ apiece. On January 4 the index rose 0.7%, yet your options would’ve soared 280%. Had the underlying investment ended up below the strike price, the options would’ve expired worthless—a total loss. It’s often called “zero to hero.”

Four months ago, Chandrashekhar Padhya used this approach to bet Rs 20,000—half his monthly pay as a hardware engineer in Ahmedabad. Padhya, 46, the sole provider for his wife and two teenage children, lost his entire investment in a single session. “The lesson I learned is that if something is too good to be true, it definitely is,” he says.

Like many individual investors. Padhya started trading after watching an online influencer, whose name he doesn’t recall. Under India’s securities regulations, only analysts registered with the regulator are permitted to provide financial recommendations. But promoters can offer education, a gray area they have exploited to great effect as they often make recommendations in private Telegram or WhatsApp groups that regulators struggle to police.

Many popular influencers charge fees for courses that range from $4 for a single introductory session to several thousand for a five- to six-month trading course. They can also team up with brokerage firms, which pay commissions for directing followers to their apps, according to Sebi.

The authorities are trying to crack down. In April, Sebi proposed banning regulated brokers from paying influencers for referrals, and it’s seeking to create a new agency to verify the returns claimed by traders. In July it mandated that brokers disclose the 90% chance of losing money.

Sebi took action against Ansari in October, citing him for improperly promoting himself as a stock market expert, promising near-certain profits and acting as an unregistered investment adviser. The agency ordered him and an associate to refund Rs 172 million they’d charged for online training courses. Ansari and his company didn’t respond to messages seeking comment.

Sebi examined Ansari’s personal brokerage account to reveal how successful he was in his own trading. Regulators tallied up the results from January to July 2023. Ansari lost $347,695.

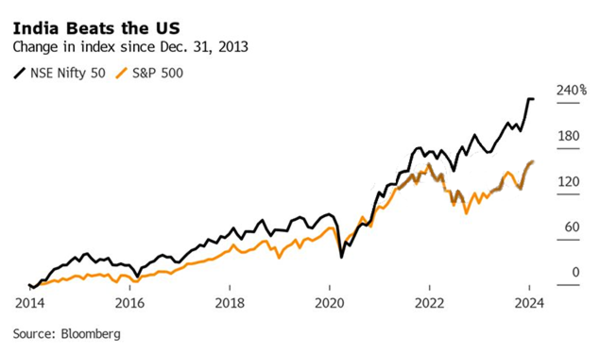

India’s rapidly expanding middle class has long stashed its savings in real estate and gold. Households have only 7% in equities and mutual funds, compared with more than 40% in Brazil and China and 50% in the US. As a result, small investors have largely missed out on India’s stock market boom, which may be fueling some fear-of-missing-out trading now. The country’s stocks have been outperforming other major markets. Over the decade ended last year, the NSE Nifty 50 index of Indian stocks has offered a 14.8% average annual return, almost 3 percentage points better than the S&P 500.

The finance industry has profited handsomely from India’s emerging culture of speculation. Consider Angel One Ltd, a publicly traded Indian brokerage. With its revenue and profit turbocharged from options trading, its share price has risen 11-fold since its 2020 initial public offering. The 20% stake of Angel One’s founder, Dinesh Thakkar, was worth $620 million in late January. (The company didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

Stock exchanges have prospered, too. The 148-year-old BSE Ltd, formerly the Bombay Stock Exchange, had its IPO in 2017. Last year its share price rose more than fourfold because of the bull run. It’s now reducing the minimum size of option trades and taking other measures to make it easier for individuals to engage in short-term buying and selling.

Since 2022, the annual tax collected from securities transactions rose fourfold, to 232 billion rupees. That sum will likely be higher in 2023 after the government in March raised the transaction tax levied on some equities derivatives.

Many established money managers worry that burned mom and pop traders will give up on stock market investing entirely. “The regulator should do more to protect retail investors,” says Ashish Gupta, chief investment officer of Axis Mutual Fund, which oversees $31 billion. “The minimum ticket size to dabble in options in India is very small. Sebi should increase this amount to raise the bar.”

But Sachin Gupta, chief executive officer of brokerage Share India Securities Ltd, says he doesn’t believe 90% of people are losing money. “How come you think that people are losing money, still they are trading more and more?” he asks. None of the major players wants to reduce trading, Gupta says. “Sebi never wants participation to go down,” he says. “Nobody wants that—not even the government, not exchanges, not your brokers.”

Sebi didn’t respond to a written request for comment. Speaking at an industry event in November, Chairperson Madhabi Puri Buch said she was “a little confused and surprised” by the continuing retail push into short-term trading rather than longer-term investment, considering the statistics show a near certainty of loss: “The odds are not in their favor at all, and the house always wins, right?”

At rush hour in Mumbai, India’s financial capital, a jingle for an options-trading academy serenades straphangers on the subway. It’s a catchy duet, sung by two famous Indian performers. “Money will flow,” they croon. “It’s the fastest way to grow.” One commuter, Sahil Kaurani, a recent college graduate working his first job, says he can’t shake the tune, which has sparked his interest in trading. “It has definitely made me curious,” he says.

Avadhut Sathe, a celebrity of the stock market boom, is behind that jingle. The song is advertising his Avadhut Sathe Trading Academy, which boasts branches in 17 cities. In online seminars with as many as 10,000 participants, Sathe looks sober and professional in a suit as he lectures on the rising heft of India’s economy and the benefits of trading for a second income.

In a January session, more than 100 people attend his five-day trading seminar at a luxury resort in the mountains of Lonavala, 50 miles from Mumbai. “Become a pro,” banners read. “Money will flow.”

The crowd includes doctors, software developers, consultants, homemakers and a cricket coach. The students sit in lines, laptops before them, while a huge screen shows live prices of stocks and derivatives. The program begins with a prayer. Sathe asks his followers to place their hands on their hearts and feel the energy in the room. “Surrender to the market god, embrace your successes and failures with a smile,” he says. A prayer in the local Marathi language flashes on the screen: “God bless us with knowledge, wisdom and acumen.”

Sathe, 53, tells his acolytes they can exploit trading patterns. Afterward, he poses for photos with his fans, striking what he calls “market warrior pose,” a capitalist twist on the powerful yoga stance.

Music fills the hall as students hum along, their arms swaying to the rhythm, concert-style. Sathe and a few others dance onstage to Hindi lyrics: “Oh, darling, love is now hurting me.”

Reeta Shah, a 57-year-old retired accountant in the audience, says she initially lost money when she started trading several years ago but is now making a profit. “Either I put my money into a bank fixed deposit and earn 6% to 8% interest,” she says, “or I need to master this skill.”

Atharava Tandle, 19, who’s studying for his business degree, says that he knows most retail traders lose money but that he believes he can control risk and be an exception. “My aim is becoming financially independent, which I believe is possible if I trade with discipline,” he says.

The students have caught Sathe’s infectious enthusiasm for options trading. “Derivatives give you leverage, and leverage with risk management is a lethal thing,” Sathe says in an interview. “There is no business that can grow your earnings four times in a year, but with well-researched derivative strategies, that is a possibility.” Sathe says his academy differs from offerings that have troubled regulators, because it provides training, not specific investment advice.

In Bengaluru, known as India’s Silicon Valley, Love Pulkit is giving index options trading a whirl. A data analyst at a tech company, he started in August after watching YouTube videos. “You can easily get up to 10%, 15% in a month if you’re good at it,” he says.

Pulkit, 27, lives with three roommates in a four-bedroom apartment, where he’s set up two screens with his laptop. “First you’ll take losses,” he tells friends interested in trading, too. He certainly has, but he waves them off. “It’s not like I should just quit option trading,” Pulkit says. “I have confidence that if I just put in my time and patience into it, I can do it.”

He has no plans to shift to steadier, safer investments. “Everyone wants to be a millionaire as soon as possible,” Pulkit says. He’s got a long way to go, judging from his record since August. As of mid-January he’d lost 400,000 rupees, or $4,400.